About Mutis Project:

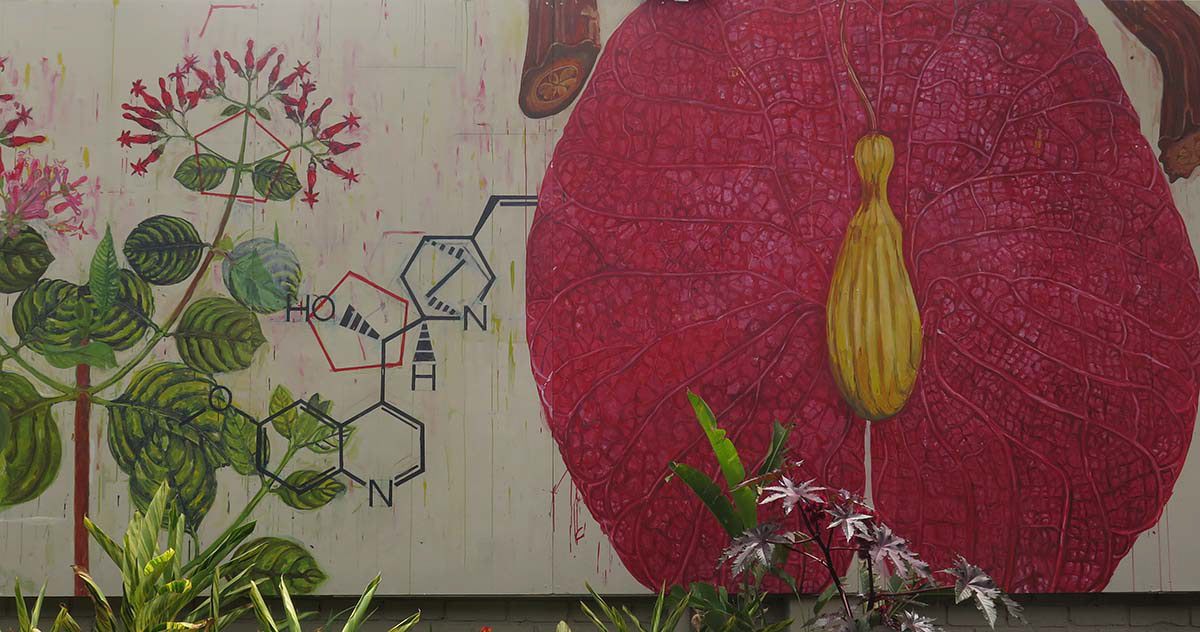

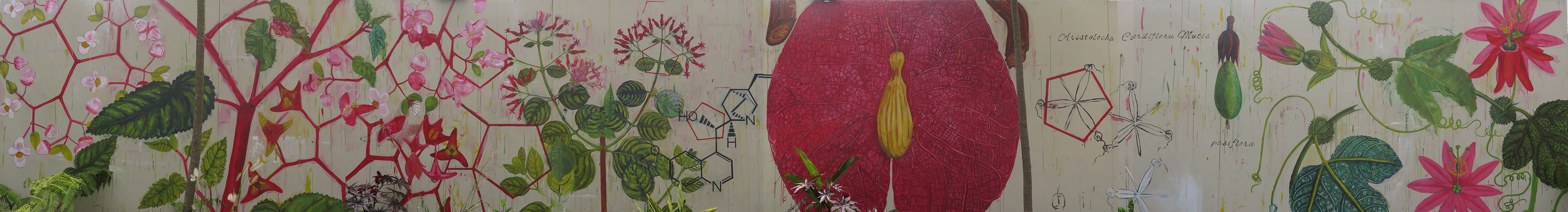

This project was a collaboration between David Delgado Architects, the University of El Rosario, and medical and science students from the same university. Two murals were developed based on the ideas, figure, and legacy of José Celestino Mutis, who led the Royal Botanical Expedition during colonial times in what is now Colombia. The murals were painted in the Faculty of Medicine and Science at the University of El Rosario. One of the murals was designed and painted with the participation of the students of the faculty, which is named in honor of the botanist and explorer. This is no surprise, given that Mutis is a foundational figure in Colombia’s national narrative.

There is a romanticized view surrounding the Royal Botanical Expedition and the figure of Mutis, as Professor Mauricio Nieto discusses in Remedios para el Imperio. He raises questions about Mutis and his legacy, critically re-evaluating the botanist’s role. These questions include the importance of Mutis’ contributions to the nation’s history, his leadership of the scientific school, and his relationship with the Spanish Crown, which largely overshadowed indigenous botanical knowledge. At a time when scientists and artists worked in favor of the Crown’s economic and imperial interests—searching for medicinal plants to benefit the Spanish Empire—they relied heavily on the traditional knowledge of indigenous communities. However, some of the expedition members, though Criollos (locally born people of Spanish descent), were trained in the Western European methods of cataloging and representing plants. Indigenous communities, however, were neither directly acknowledged nor benefited from these expeditions.

Additionally, in 2019, informal conversations took place with Carlos Rodríguez, the director of Tropembos Colombia, who possesses extensive knowledge and experience with various communities in the country, particularly in the Amazon rainforest. During these conversations, questions were raised regarding traditional indigenous visual representations of plants. Carlos noted that while contemporary indigenous communities have figurative representations of plants and biodiversity, these are not found in traditional visual forms. The indigenous communities living in the territories explored by the Royal Expedition approached and represented plants in ways that starkly contrasted with Western standards. For example, in their traditional visual expressions, such as drawings, Amazonian indigenous peoples rarely depicted plants as individual entities. Instead, they used geometric abstractions to refer to the broader landscape. This suggests a different way of understanding and representing plants, one that goes beyond the European visual canon. Geometrical representations, often directly linked to plants, played a key role in their visual language.

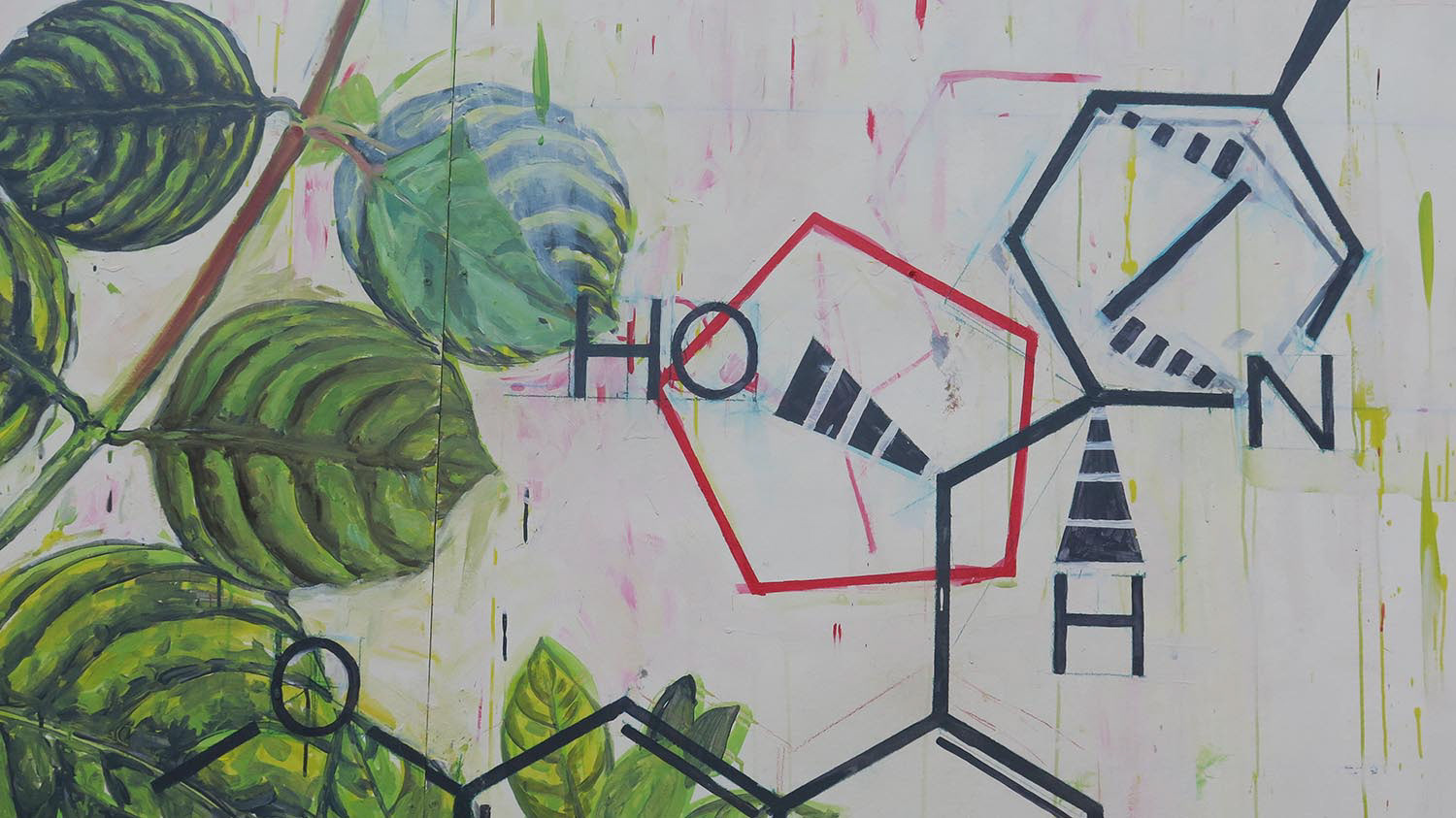

I found it fascinating that European scientific methods of visually understanding and representing chemistry also involved geometric abstractions, as seen in the visual language used to describe quinine (Cinchona) and its properties. Similarly, indigenous peoples used visual patterns to refer to a plant and its properties, reflecting a shared human inclination to use abstraction to convey knowledge.

In both European and indigenous approaches, visual representations have been significant in reflecting humanity’s relationship with plants and their properties. Plants have played crucial roles in various cultural contexts—as medicinal, therapeutic, hallucinogenic, and ritual elements, among other uses. Across cultures, plants hold immense importance, and despite differences in how they are approached, there is a universal appreciation for their diversity of colors, forms, and functions.